- Blog

This article will introduce you to the concepts and principles that make up a well thought through periodisation plan. It is clear to see after studying the origin and history of periodisation that periodisation is a very principle-driven approach to the planning and preparation of training.

If we take a look at the scientific principles established by some of the coaches and scientists previously mention such as Kotov, Matavie and Verkashanski, and combined them with some of the forward-thinking and modern-day findings from Stone, Bompa, Kemmler, Poliquin, this will provide insight as to how periodisation has evolved to deal with the demands of the modern-day sport. It will also provide you with a clearer understanding of how to approach periodisation.

Periodisation concepts are theories that are generally supported by science however they are malleable and can change over time with enough new research to support that change. Before we discuss concepts that support the management of periodisation plans let’s first discuss the term supercompensation.

What is Supercompensation?

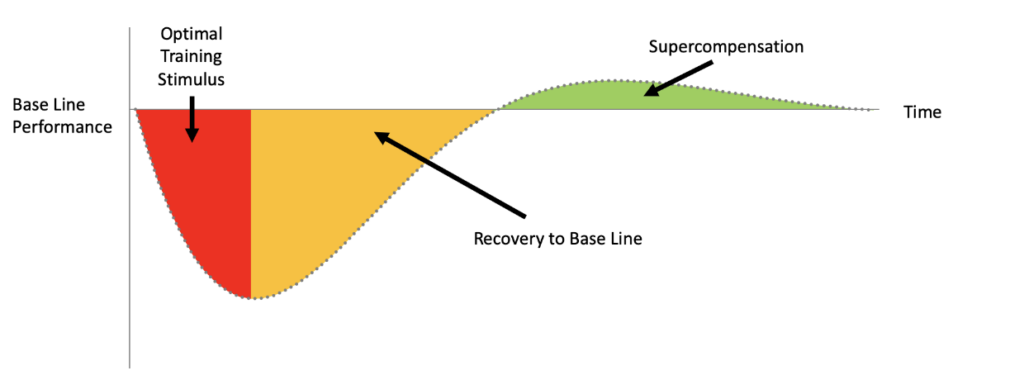

Supercompensation is when the body encounters stress, from training. Following the exposure to that stress, the body will experience fatigue like effects from the overreaching nature of the training.

During the recovery period, the body recovers to a point beyond its original level of fitness hence the word ‘super’. If managed correctly the athlete continues to improve on their fitness qualities over time.

Let’s next look at Periodisation concepts that support the management of Supercompensation.

Fitness Fatigue Paradigm

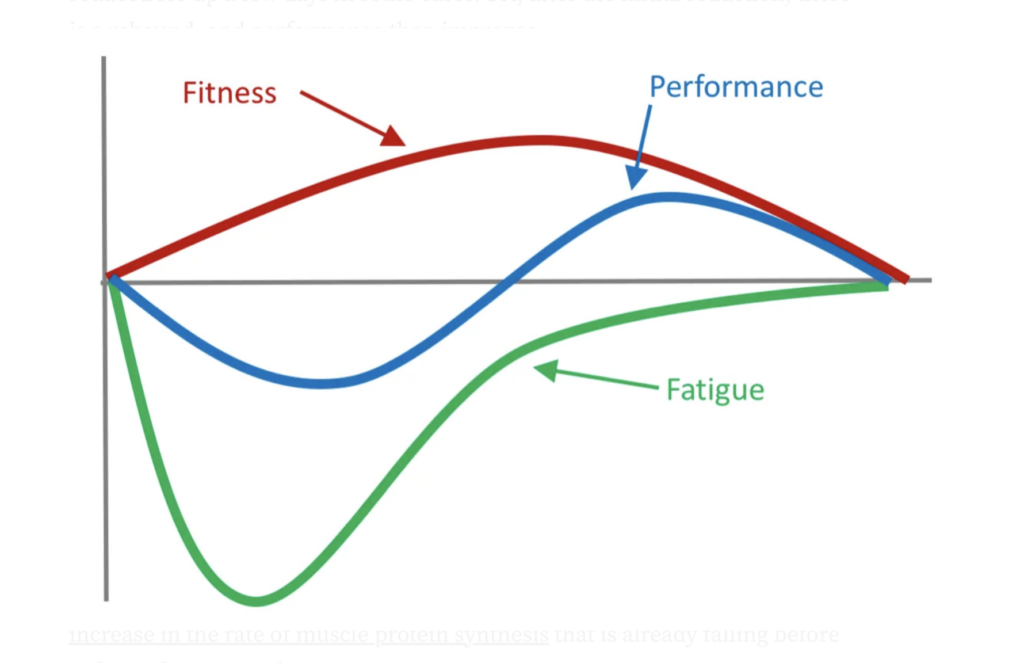

The first periodisation concept we are going to look at is the fitness fatigue paradigm. This concept currently is the most prevailing theory that supports the adaptation to training. Why is because the fitness fatigue paradigm suggests that an athlete’s preparedness or redness to train may be evaluated based on the aftereffects of training?

This means that both fitness and fatigue have an inverse relationship and therefore, implies that training strategies that minimise fatigue and maximise fitness will have the greatest potential to maximise an athlete’s preparedness. Athlete preparedness can be described as an athlete’s ability to train or perform near or at 100% of their performance capacity.

The fitness-fatigue model below is explained with the sum of two curves, one representing fatigue one representing fitness improvement. Only once the fatigue effect has dissipated is it possible to see the fitness effect.

Fitness Fatigue Paradigm

The first periodisation concept we are going to look at is the fitness fatigue paradigm. This concept currently is the most prevailing theory that supports the adaptation to training. Why is because the fitness fatigue paradigm suggests that an athlete’s preparedness or redness to train may be evaluated based on the aftereffects of training?

This means that both fitness and fatigue have an inverse relationship and therefore, implies that training strategies that minimise fatigue and maximise fitness will have the greatest potential to maximise an athlete’s preparedness. Athlete preparedness can be described as an athlete’s ability to train or perform near or at 100% of their performance capacity.

The fitness-fatigue model below is explained with the sum of two curves, one representing fatigue one representing fitness improvement. Only once the fatigue effect has dissipated is it possible to see the fitness effect.

Once fatigue has dissipated athletes may experience a supercompensation effect to training.

Stimulus Recovery Adaptation Curve.

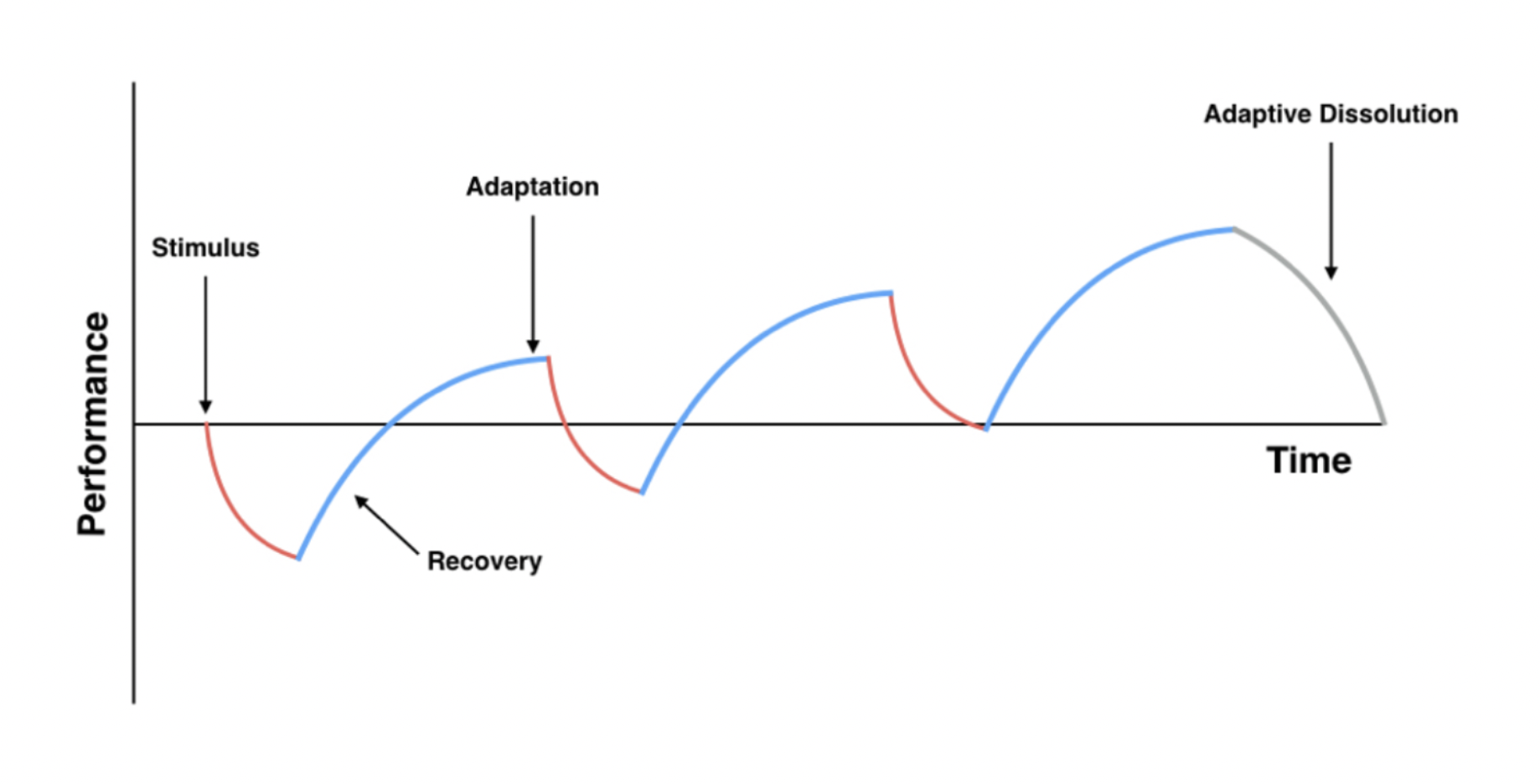

The second concept we need to understand is the SRA curve or Stimulus Recovery Adaptation curve. The SRA curve is a sports science term describing the process through which our bodies respond to training. When we train we introduce a stimulus or stress.

Our bodies then respond to this stress by making various adaptations. If our bodies respond adequately then super-compensation occurs and we grow stronger while also being able to deal with the initial stress.

In conclusion, both the fitness fatigue paradigm and the stimulus recovery adaptation curve are both methods of managing fatigue so your athlete continues to adapt or supercompensaint to training over time.

The fitness fatigue paradigm allows you to look at the management of fatigue very acutely or on a session by session basis while the stimulus recovery adaptation curve allows you to analyse training over a longer period of time on a block by block basis.

Next, let’s have a look at some of the main training principles that must be followed when piecing together your periodisation plan.

Overload:

The first principle is the principle of overload which can be defined as constantly applying an appropriate stimulus resulting in physiological and psychological adaptation to training. When an overload is applied in the form of intensity or load characteristics such as improved force, rate of force development and power are evident.

When an overload is applied in the form of volume characteristic such as improved work capacity is evident.

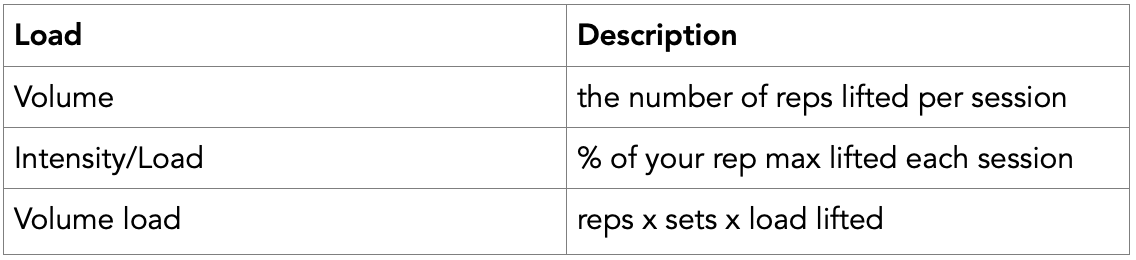

How do we quantify intensity and volume?

Intensity or load:

Intensity or load is simply the amount of weight prescribed to an exercise set. The intensity or load applied to an exercise program is a critical aspect of the periodisation and training plan as it dictates the adaptation.

For example, if we ask an athlete to lift 95% of their 1 repetition max we can safely say that the athlete will be eliciting the adaptation of strength from that given prescription of intensity or load. However, if we ask the same athlete to lift 55% of their 1 repetition max we can safely say that the athlete will be eliciting the adaptation of hypertrophy from that prescription of intensity or load.

Furthermore, an inverse relationship must exist between the amount of weight lifted (load) and the number of repetitions performed (volume). This means both training variables load and volume cannot consist together with in the same prescription of exercise. If intensity or load is high and strength is the goal volume must be low.

If the volume is high and hypertrophy is the goal load then must be low. Load should always be prescribed based on your athlete 1-3 repetition max.

Volume:

Training volume is simply the sum of the total number of repetitions performed during a training session multiplied by the resistance used in either kilograms or pounds. Training volume is an equally important variable as it dictates adaptation in the form of mechanical vs metabolic stress. Mechanical stress is a result of the load being high usually from max strength type training and the volume is low whereas if the volume is high we have a greater chance of creating metabolic stress which is one of the main drivers of hypertrophy.

Specificity:

The second principle is the principle of specificity which deals with the degree of similarity between the sport and training such as metabolic and mechanical. The closer you can bring both the metabolic and mechanical aspects of training to the sport the greater the transfer of training effect you will get.

To make training specific progressive movement skills should be applied to all blocks of training. Technical progression of movement skills shows a progressive increase in motor control ability through various movements associated with the sport from general to specific. An example of this is during the first block of training hypertrophy or strength endurance type training for the lower body will develop the muscle architecture required to deal with the load in an exercise such as the back squat. The back squat is considered a general strength exercise.

Block 2 will progress that back squat movement to increase the load and in turn, develop maximal strength.

Block 3 would improve the explosive intent at which that squat pattern is being performed by introducing accommodating resistance in the form of bands and chains. In turn, this would develop a strength speed quality that is slightly more specific to sports. Finally, block 4 would introduce plyometrics and sprinting type exercises to develop explosive strength and reactive strength qualities. This type of training would be considered highly specific to the sport or in other words adhere to the principle of specificity.

An important rule that must be followed when approaching the technical progression of movement skills is that a breakdown in technical ability at any stage in the above progressions will hamper and affect any further progression of that skill. Once training becomes specific we get a transfer of training effect which suggest that the specific exercise selection being prescribed to the athlete is carried over into the performance of the sport.

Once the general to specific continuum is followed a phase potentiation effect should take place in each subsequent block of training. For example block 1 of hypertrophy will supercompensation the following block of training which is strength which will supercompensation the following block of training which is power and so on.

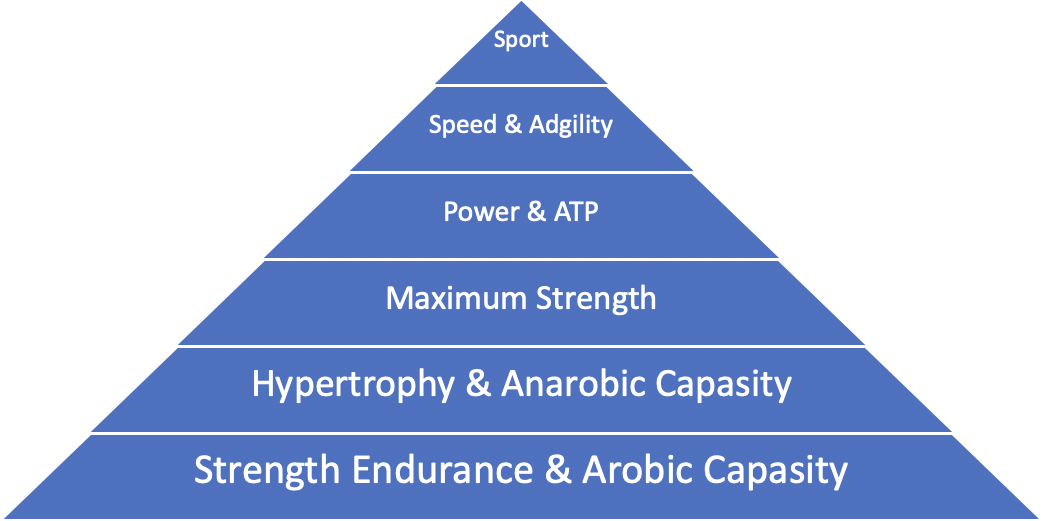

A rule to be aware of when planning your phase potentiation is each fitness quality must be developed appropriate and to the fullest of the athlete’s ability, if this rule is not followed an early to ripen early to rotten scenario will occur where the athlete may find a very acute response from moving onto the next block of training but the long term effects will be detrimental to long term athletic development. The second rule of phase potentiation is you cannot skip a fitness quality within the system of higher archie of fitness qualities. Please see the diagram below for an example

Variation:

The third principle is the principle of variation. Variation is how we manipulate the overload and the degree of specificity. Variation in training cycles is arguably the most important aspect of periodisation. Variation in training directs the athlete towards a specific goal for example power or speed.

Variation also helps manage fatigue, too much fatigue will affect adaption and you run the risk of injury with your athletes. The presence of variation in a periodization plan allows us to manipulate the variables such as load and volume to elicit a specific adaption. Let’s look at how we manage variation from the day, week, month, year and so on.

To achieve variation, training needs to be broken down into periods or small blocks of training where very specific goals can be achieved.

Quadrennial Cycle:

The first period of time you should always aim to map out for your athletes is the quadrennial cycle which reparents a 4-year duration of training. Traditionally coaches who focused on the quadrennial cycle were Olympic coaches who trained track and field sports athletes due to the long duration of time (4 years) between Olympic games.

However, the planning of quadrennial cycles has become more evident in the field, court and combat sports in recent years, especially with adolescent athletes due to the long term athlete development qualities that can be achieved by a well thought out periodisation quadrennial plan.

Macrocycle:

Next, we have the macrocycle which represents roughly 1 year of training, any athlete regardless of their sport that either competes once per season or multiple times a season such as field-based sports like soccer or rugby should have a detailed macrocycle. Each macrocycle cycle should encompass the preparation of athletes, starting with their pre-season training where qualities such as aerobic capacity and strength endurance should be developed.

Following this in-season training athletes should be exposed to qualities that will improve different performance qualities required to play the sport such as strength, power, speed and anaerobic energy system development.

Mesocycle:

The mesocycle cycle of training represents the block of training and can last anywhere from 2 weeks up to 8 weeks. This is the most commonly used form of periodisation or the periodisation planning that we as coaches engage most with. Goals within the mesocycle should be highly specific such as during preseason the goal should be to build a level of endurance and robustness so the next mesocycle will be able to build on the previous block of training.

Micro Cycle:

A microcycle is the shortest training cycle, typically lasting a week to facilitate a focused block of training. An example of this is an endurance block where a cyclist strings three or four long rides together within one week to progressively overload training volume.

Daily:

Lastly, we have the days in which the single training session or sessions may take place. These sessions could be stand-alone conditioning or weight room based resistance training sessions or a combination of both.

About Author:

Shane Cahill is the director of education and operations at APEC. An ex-professional athlete, Shane spent the majority of his professional rugby playing career in the UK playing in the RFU Aviva Premiership and Championship.